Localised Amyloidosis

Summary

Localised amyloidosis refers to a disease where the amyloid forming protein is both produced and deposited in the same local environment.

Most forms of localised amyloid are due to deposition of immunoglobulin light chains (AL) thought to be produced by foci of low-grade monoclonal or oligoclonal B-cells or plasma cells which secrete monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains in the immediate vicinity.

This section of the website will focus localised AL amyloid where in general:

- Deposition occurs in mucosal, glandular and cutaneous tissues

- Progression is slow

- The process does not become systemic

- Management is observation or localised in nature

- Systemic chemotherapy is not indicated

- Survival is excellent

Other types of localised amyloid can occur in almost any part of the body and are derived from a broad range of (normally endogenous) proteins and have different aetiologic factors.

Localised Amyloidosis: in detail

Pathophysiology

Most forms of localised amyloidosis are due to deposition of endogenous proteins most commonly immunoglobulin light chains, thought to be produced by foci of low-grade monoclonal or oligoclonal B-cells or plasma cells which secrete monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains in the immediate vicinity.

Localised AL usually occurs in the mucosa and the aetiology is uncertain but it may be that local epithelial “trauma” or prolonged antigenic stimulation from infection or inflammation results in such oligoclonal or low-grade monoclonal immunoglobulin production.

Localised amyloid can also consist of other endogenous proteins such as the semenogelin amyloid found in the seminal vesicles and atrial natriuretic peptide amyloid produced in the cardiac atria. These other types of amyloid have different aetiologic factors such as aging.

Less commonly, localised amyloidosis can also occur due do deposition of exogenous proteins such as AIns where synthetic insulins misfold to form amyloid deposits at sites of subcutaneous insulin injection.

Occasionally localised AL deposits are seen infiltrating plasmacytomas or lymphomas. In this circumstance the presence of amyloid deposition is not necessarily indicative of systemic disease. 1,2,3

In the majority of cases of localised AL (even those formed in plasmacytomas or lymphomas) there is little or no histologic evidence of the B or plasma cells producing the amyloid. A hypothesis for this phenomenon is that toxic oligomers are produced during AL amyloid formation which lead to apoptosis of the clonal cell. Consequently, localised AL amyloid has been described as “a suicidal tumour cell creating a self-limiting neoplasm”.4

Clinical Presentation

Localised amyloid deposits can occur almost anywhere in the body including the brain and heart but the most commonly referred type, localised AL, occurs in mucosal, cutaneous and glandular tissues.

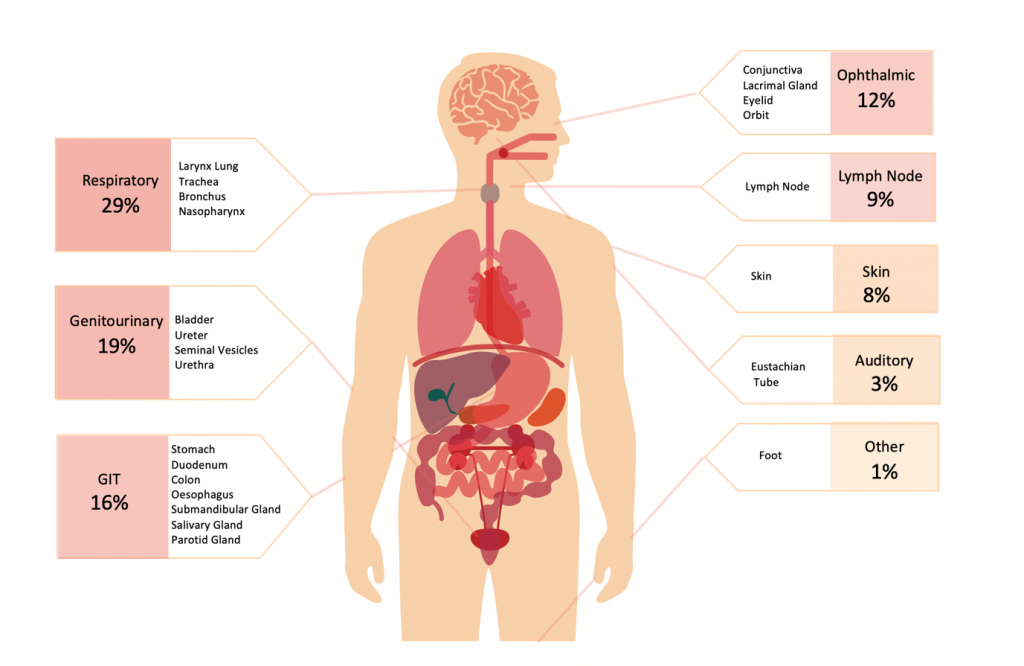

In an AAN cohort analysis2 the most common organ sites were the;

- Laryngo-tracheobronchial tree (dysphonia, cough, haemoptysis)

- Genitourinary tract structures such the bladder and ureters (haematuria, obstruction)

- Gastrointestinal tract (GIT bleeding but often an incidental finding)

- Orbit and adnexal structures such as the eyelids and lacrimal glands

Diagram 1. Sites of localised amyloid in a cohort of localised amyloid cases referred to AAN centres up until 2016 (n=65). Light chain was the constituent protein in almost all cases with semenogelin a distant second. 2

The GIT is commonly affected by both localised AL and a range of systemic amyloidoses (AL, AA, ATTR) and so when GIT amyloid is identified it is important to differentiate between localised and systemic disease.

Diagnosis

It is critical that patients who present with presumed localised amyloid deposits have a full work-up to investigate for the presence of systemic disease including testing for monoclonal gammopathy, cardiac biomarkers, urine assessment for proteinuria, and clinical examination for peripheral and autonomic neuropathy or soft tissue infiltration.

To differentiate between localised AL amyloid over systemic AL the following are not typically present in localised AL:

- Vital organ involvement of the kidney, heart, liver or nerves

- A remote plasma or B-Cell clone producing an amyloidogenic light chain

- Vascular-only amyloid deposition on biopsy

These differentiating points are useful when working up most but not all cases of localised amyloid. For instance, the cardiac atria can be involved by age related localised ANP amyloid. Furthermore, the presence of a monoclonal gammopathy can make it difficult to determine if the AL amyloid is localised with a benign unrelated monoclonal gammopathy or representative of systemic AL. In such cases, it is useful to compare the amyloid protein’s light chain isotype to that of the monoclonal gammopathy isotype.

Prognosis

Localised AL amyloid is usually slowly growing and associated with low volume deposits that are minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic in nature.

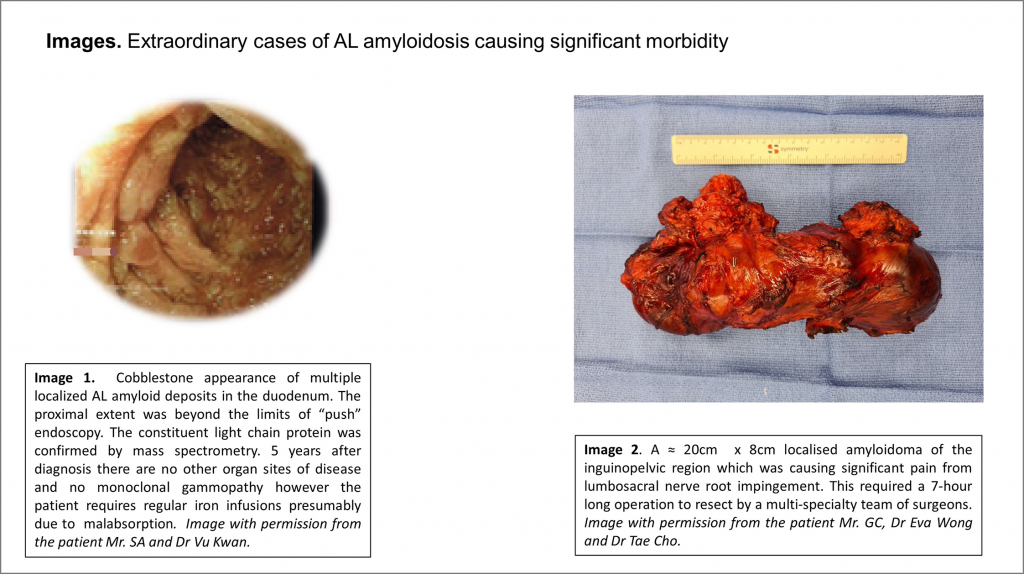

However, rare presentations with rapidly growing or large volume amyloid deposits can cause significant morbidity or life threatening complications via;

- Bronchial obstruction

- Bladder haemorrhage

- Ureteric obstruction

- Laryngeal obstruction

- Loss of voice

Local amyloidosis rarely progresses to systemic disease but local recurrences as well as multiple sites in the same tissue/organ are not infrequently observed. 1,2,5 In an AAN cohort analysis, 6/65 had bilateral disease and the majority involved the exocrine glands (1 each for parotid, lacrimal, buccal mucosa, minor salivary, submandibular glands) followed by deposition in the lung or mucosa.

Progression to systemic AL is only rarely observed. Only 1 out of 606 in the largest published case cohort progressed to systemic AL and this patient presented with lymph node disease1.

Treatment

Localised AL amyloidosis is most often simply observed and local intervention is only indicated when symptoms or organ dysfunction occurs. 1,2,5

These focal surgical and interventional measures can be divided into approaches that remove or debulk the amyloid (through resection, laser therapy or other specialised techniques such as intravesical bladder chemical therapy) or that provide supportive care (eg bronchial or ureteric stenting).

There is no proven role for radiotherapy or chemotherapy in the routine management of these patients, although certain severe presentations (e.g. unresectable airway obstruction) may justify a trial of local radiotherapy. 1,6,7

Systemic chemotherapy is rarely indicated and only applied in the very specific circumstance of localised AL produced by a systemic clonal disorder that is causing significant morbidity eg amyloidomas of the lung derived from MALT lymphoma causing respiratory compromise.